Journalist and educator Mary E. Jones Parrish's account of the massacre targeting the Black residents of the Greenwood area of Tulsa, Oklahoma, captured the horror and the implications to wealth. After fleeing in "a hail of bullets" and escaping to safety, she and her 6- or 7-year-old daughter returned days later in a Red Cross truck that drove through a white area of the city.

"Dear reader, can you imagine the humiliation of coming in like that, with many doors thrown open watching you pass, some with pity and others with a smile?" Parrish wrote in her book, "

"There were to be seen people who formerly had owned beautiful homes and buildings, and people who had always worked and made a comfortable, honest living, all standing in a row waiting to be handed a change of clothing and feeling grateful to be able to get a sandwich and a glass of water," Parrish wrote.

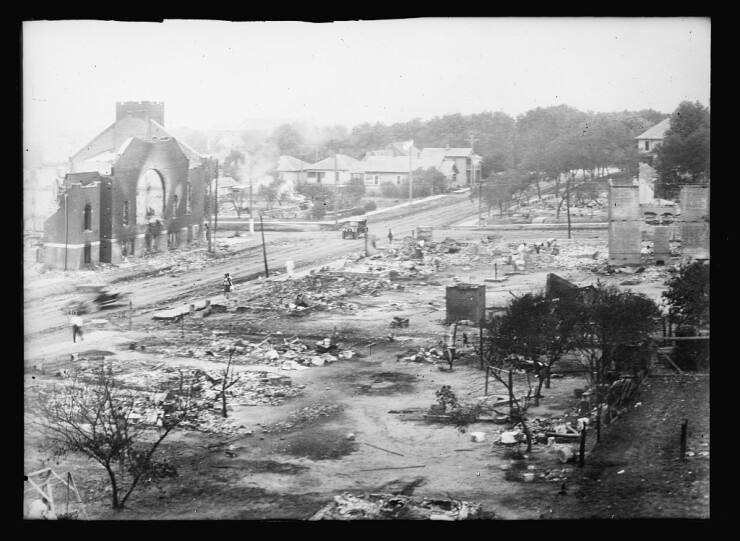

More than a century later, the racial trauma connected to money endures in Tulsa and throughout America. A white supremacist mob killed hundreds of people while robbing them of the means of building wealth. In the dismantling of a 35-block neighborhood, rioters deputized by local law enforcement leveled 1,200 homes, looted 300 others and ruined 191 businesses.

The clashes on the night of May 31 followed by the attack and decimation of Greenwood the next day occurred over two days out of an entire history of a country marked by money and race. The silence and secrecy in the wake of the atrocities reflect an amnesia among some Americans about the brutality and subtleties surrounding the intersection of race and wealth.

On the 102nd anniversary of the massacre and with a court case pending that

In the mob's invasion of Greenwood, generational wealth got "systematically thwarted" and "was taken away, it was stolen," said Jim Casselberry, the CEO of

"Tulsa," Casselberry said, "is an illustration of things that have happened in this country, that continue to happen in this country, and that, in the aftermath, people don't know about it. Stories have been hidden about it."

For planners, an understanding of clients' generational trauma and associations with wealth often informs how to serve investors, said Natalie Haggard, a senior wealth advisor based in the

That trauma "needs to be considered in the conversation of how that person relates to wealth and how that person accumulates wealth and how that person moves through the world at all," Haggard said. "My job is to listen, to hear both what they're saying and what they're not saying about their experience with money, their experience with trauma, in order to serve them well."

The scale of wealth lost

Victims and their families as well as Jones Parrish and later historians have shed greater light on the massacre and its context, which stretches back to the forced relocation of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole nations in the 1820s and 1830s. Enslaved African Americans moved to Oklahoma with the wealthiest members of the tribes.

Following the Civil War and a land allotment process to tribe members and freedpeople, two dozen Black towns sprang up around Indian Territory with the majority "in the Creek Nation, the nation most inclusive of and friendly to people of African descent," the University of Pittsburgh professor Alaina Roberts wrote in her 2021 book, "

The Black-owned businesses in a section of the oil boomtown of Tulsa got the name "Black Wall Street" due to "the financial success of the rooming houses, movie theater, grocery stores, auto repair shop and dentists' offices that lined its avenues," Roberts wrote.

"It was these very accomplishments that had long provoked the envy of the whites in the community," the book said. "These white settlers retaliated using the pretext of an African American man's purported assault of a white woman — a common excuse for violence — to massacre over a hundred Black women and men."

Available resources on what caused the incident include the work of

"The Negro in Oklahoma has shared in the sudden prosperity that has come to many of his white brothers, and there are some colored men there who are wealthy," civil rights activist Walter White

Direct economic losses added up to between $2.2 million and $3.2 million in 1921 dollars, or a range of $32.6 million to $47.4 million today, according to

In addition to the "horror beyond all calculation" of the deaths in the massacre, another "important and often neglected dimension to this history is the devastating effects of destroyed communal wealth," authors Andre Perry, Anthony Barr and Carl Romer wrote.

"Even as the massacre itself becomes better known, much of the remaining story of Greenwood is still left untold," the Brookings authors wrote. "In particular, little attention is given to subsequent events in Tulsa, including the rebuilding of Greenwood by its Black residents, followed by its second destruction — this time at the hands of white city planners during the 'urban renewal' period of the 1960s to 1980s. In both periods of destruction, important Black capital that undergirded the community was lost, as were opportunities for wealth-building for Tulsa's Black residents."

Additional studies have found alternate means of measuring the wealth impact of the massacre. It and 37 other massacres, lynchings and violent incidents targeting African Americans "account for more than 1,100 missing patents," along with a contraction of valuable inventions "in response to major riots and segregation laws,"

The

Contemporary median Tulsa home values for the 1,200 demolished in the attack, plus a calculation of other assets such as cash and personal and commercial property, adds up to as much as $150 million to $200 million in damages in current money, according to the study, which pointed out that Tulsa was far from the only scene of racist violence in its day.

"These massacres of African American communities not only led to the loss of innocent lives, but they also destroyed the economic prospects for future generations," authors Chris Messer, Thomas Shriver and Alison Adams wrote. "In the many cities such as Tulsa where riots and massacres occurred, white citizens and officials effectively wiped out the accumulation of wealth."

Money and trauma

The opening of Tulsa's

"When you are harmed and hurt, reconciliation is not a word you can hear. It's a cuss word. It's a stain on your heart," said Vanessa Adams-Harris, the director of outreach and alliance at the

Writers have captured that economic trauma in works about the massacre or books that gesture toward it. The

"'Heat always rises — those on top in society always feel the heat and pressure when we Negroes succeed and do well,'" the character said. "'Unfortunately, when they feel the heat and pressure, they lash out verbally and physically. They must stay on top socially, educationally, politically and economically — at all cost.'"

Jones Parrish's book contains individual victims' stories of what they lost in the massacre, such as an assistant county physician named R.T. Bridgewater.

"It seems that several things have been said and done to discredit and to kill the influence of the men who have large holdings in this burned district," he wrote.

Such connections with the past can reverberate on the descendants of victims of the massacre. In

"It's kind of trippy in a way because my great-grandfather and his wife and five children fled from horrific violence," Bryant said. "He settled in a community that's in the ZIP code 14208, where this person committed this abominable act a few weeks ago. And so here we are, 101 years later, still fighting against racial violence, still fighting for the rule of law and a search for justice."

Calls for reparations to survivors and their families have grown over the past several decades. Advocates point out similarities to other groups that have received compensation for atrocities, and they often cite the impact of the construction of a freeway through the center of Greenwood as a further means of undercutting the area's wealth decades after the massacre.

Some select groups that have suffered in times of war or the outbreak of violence have received compensation, according to

Residents had rebuilt Greenwood in the '30s and '40s to the point that it was home to "unquestionably the greatest assembly of Negro shops and stores to be found anywhere in America," according to a business directory from the time quoted in the Harvard report.

The community "never recovered to its prior size or magnitude" after the

With the condemnation of property starting in the 1950s and the city's construction over the next 20 years of seven expressways in a ring around the downtown under financing primarily from the federal government, the highways "bound the remaining population in Greenwood's core and created dead space under the overpasses and near the exits," a

In that sense, Tulsa resembled many American cities in which interstate highways displaced Black and other minority residents and enabled white flight to suburban areas that often had

Efforts to obtain reparations for Tulsa victims through court cases or legislation have failed, though.

Led by a nonprofit organization called the

"It is completely to eradicate the destruction that was done to an entire community," Solomon-Simmons said at the bar association event last year. "That includes money in a victim's compensation fund; that includes land trusts; and that includes removing highway 244 that was put into Greenwood many, many years later to continue the work of the destruction of the massacre; that includes mental health training; that includes abatement of taxes. Why should our people pay taxes to the very government that destroyed them and never rebuilt them? It includes scholarships for families and descendants of those who have been impacted. It includes a declaration from the court that says, 'Yes, this actually happened. You're responsible for it, and you need to fix it.' That's valuable to us."

The special circumstances of Oklahoma

In addition to the lawsuit seeking reparations, Solomon-Simmons and Justice for Greenwood have

Historian Angie Debo's books, "

Railroad lines first reached Tulsa, which is a Creek name, in the 1880s, and its emergence as "an important shipping point for cattle" was "still another type of foreign settlement within the Creek domain," Debo wrote in the history of the tribe. The discovery of oil around the turn of the century fueled the growth of Tulsa from 1,930 residents in 1900 to 18,132 a decade later and 35,000 after World War I.

The tribal nations largely opposed the allotment of the land, although some members became very wealthy from oil. In a Senate hearing about allotment after the Civil War, the Creeks cited "their own memory of their losses in Alabama" prior to their removal as the reason they didn't want the land divided into individual tracts, Debo wrote. Black freedpeople who were officials in the Creek government, law enforcement officers and had other prominent jobs participated in the hearing as part of the delegation as well.

"As a Supreme Court justice, several members of the Council, a lighthorseman, etc, who had once been slaves, testified to their full participation in the government, their growing herds of livestock, and their unrestricted use of all the rich land they wanted, even a Reconstruction senator could find no cause of complaint against the 'rebel Indians,'" Debo wrote. "It was plainly apparent that the Negroes had opportunities here for untrammeled development existing in no other part of the United States."

Not every tribal member receiving land in the process made a fortune, though. Debo's book chronicled how white land speculators wrested some tracts from Native people and enrolled African Americans for a fraction of their worth — a memory recalled by tribal members today.

"We like to treat people like we want to be treated," said Danny McCarter, a retail interpreter at the

Others capitalized on their holdings. Money poured "into the hands of people who a few years ago were as poor as the proverbial small rodent in the sanctuary," according to a 1914 article in the NAACP's publication, The Crisis, entitled "The Negro and Oil" and excerpted at the Greenwood Rising museum in Tulsa.

"Indians, white men and Black men are being made into millionaires almost overnight in Oklahoma these days, and Uncle Sam is acting as the treasurer in this fascinating game of getting rich without doing a stroke of work," the article read.

Tulsa is an illustration of things that have happened in this country, that continue to happen in this country, and that, in the aftermath, people don't know about it.

The land allotment process and subsequent migrations of other African Americans who flocked to Black towns springing up around Indian Territory contrasted with other parts of the country, where there were broken promises of tracts for freedpeople in the wake of the Civil War.

"Oklahoma had the largest number of all-Black towns and communities and cities in the United States at that time, in part because of the land allotments that were given by the government," Nia Clark, the host of the "

Businessmen

"Since city laws forbade Blacks from shopping in areas other than Greenwood, Black-owned businesses flourished," the Harvard Business School study said. "Although Greenwood had no formal financial institutions, author and educator Booker T. Washington dubbed the area 'the Negro Wall Street of America' while visiting in 1913."

The decimation of Greenwood in the massacre robbed the area of wealth, as well as "the Oklahoma Black memory of self-sufficiency, economic success and racial coalition," Roberts wrote in "I've Been Here All the While."

"The massacre was not taught in Oklahoma schools, nor was the awe-inspiring reality of Black Wall Street," Roberts wrote. "This was not the first nor the last act of racial violence by whites against Black women and men living in the space of the former Indian Territory. But as the largest destruction of Black wealth in the region (and, according to economic historians, in the country) and the deadliest in American history, the Tulsa Race Massacre represents the end of the largest representation of what Blacks were able to build economically and socially within Native spaces and under tribal jurisdiction within their extended Reconstruction."

Silence about the massacre

Historians and many Tulsa residents say that people around the city avoided discussing the massacre for decades, which led to confusion about the identity of the attackers and added to the unresolved nature of the trauma.

Addressing the unpunished perpetrators has "been a continual conversation in the city," but the passage of time and the fact that "the story was covered up for so long" adds to the difficulty, according to Mikeale Campbell, a lifelong Tulsa resident who's now the program manager for

"Those things aren't talked about," Campbell said. "It's hard to make any clear lines to have proof, so there's speculation and then nothing else."

The massacre and the succeeding decades reflect the "brutal history in this country" of "an endless wealth suck" out of Black neighborhoods, said Dan Houston, a partner at an economic analysis and strategic planning consultancy called

"You meet German immigrants in Brazil and no one wants to tell you what Granddad did," Houston said. "Whatever grandad did, we don't want to ask. And Tulsans don't want to ask."

A newer resident, tech professional Jenniffer Nevarez, moved to the city three years ago from Florida through the

The confrontation felt "very territorial" and made Nevarez feel "out of place" and think "maybe I should not be here," she said.

"I'm sitting here in this historic place, and as I learn more and more about it, I think, 'Why isn't this talked about more?'" she said. "The more you learn about what happened, the more palpable it feels."

Ann Browning lived in Tulsa for around 40 years, mostly in the tony Maple Ridge neighborhood where oil-rich families had built mansions. The property deed to her family's home mentioned a freedperson who once owned the land, according to Browning.

"I have never understood what caused the race riots," she said. "It was not talked about. We knew about it because our neighbors had sheltered their help in their basement."

The act of working in other people's homes often evoked the trauma of the massacre, too, Solomon-Simmons said on the panel.

"There were survivors who were talking about going into white homes as repairmen or maids or butlers or delivery drivers 30, 40, 50 years after the massacre and seeing things that were taken from their homes," Solomon-Simmons said.

Lessons for the future

Many Tulsans are trying to set a new course for the city and the country through the examination of history and the repurposing of landmarks. For example, Greenwood Art Project artists William Cordova and Rick Lowe turned the "

"Is it fair, I ask myself, that on the one hand some of us should draw upon a legacy of affluence and opportunity, and be recipients of those blessings and gifts which provide the roots and wings tantamount to happiness and success — and yet not also bear in some way the shadows of that legacy, which include injustice and violence done to others?" Jeffrey Myers, a Presbyterian pastor,

The

Houston, the economic analyst, praised the Skyline Mansion as the reclamation of "an open sore in the neighborhood." The massacre, plus succeeding decades of racial discrimination in housing, education and other areas demand some form of restitution, according to Houston.

"We owe a lot of people for a lot. Slowly bleeding people of their opportunities in life is in some ways worse than showing up with firebombs," Houston said. "A lot of people feel like, 'Oh there's a museum now, so we're done.' … That's a fairly universal American sentiment."

Haggard, a financial advisor who's a member of the Chickasaw Nation, has been trying to be "more introspective" about her family's history and the resources necessary to build wealth, she said. She doesn't know if her great grandfather, who, according to family legend, got the last name of Smith given by default to many Native people, received a land allotment. He spent his childhood in an orphanage, but he later would "pass wealth on to several generations" of Haggard's family through construction, bricklaying and real estate ventures, Haggard said.

"One of the things that I've been thinking about a lot just in general is the privileges that I have had in my life that have gotten me to sit where I sit, and how those privileges may not have been available to other people," she said.

Human beings created the wealth disparities of today, which means that people can eliminate them as well, according to Casselberry of Known. Investing resources in a community boosts homeownership rates and brings other benefits, he noted.

"If you think about what happens if you're able to reinvigorate a community — what happens when you do that: You put more people on the tax rolls, more services and businesses develop, employment rates go up, people buy products and services. The overall economy is then thriving," Casselberry said. "People have lost sight of that, if you lift someone up who is left behind, it doesn't hurt you. The reality is, it helps you."