Are cluster bombs a good thing? In a world exploding with measurements of how beneficial companies are for the environment and society, the answer is sometimes yes.

Several global asset managers whose funds carry a sustainability-themed label have tiny stakes in

One might think a manufacturer of

The gauge, run by Solactive, a German index provider, tracks the financial performance of companies that operate “in accordance with market standards” on ESG screens, including the Paris Climate Agreement and the United Nations Global Compact — a voluntary pledge by companies to move the needle on global issues including climate change, human rights violations and corruption. Solactive’s ISS Emerging Markets Carbon Reduction & Climate Improvers Index also weeds out companies according to their “significant involvement in defined sectors.”

Its June 6

Other funds that market themselves as hewing to ESG and sustainability goals also own stock in companies that some investors might find puzzling. Some 266 of the 557 U.S. sustainable funds tracked by Morningstar Direct hold shares in oil or gas companies, likely under the logic that shareholders with good intentions can nudge a company on environmental and social issues, an ESG approach known as “engagement.” More than 160 sustainable funds hold defense industry stocks. One fund dedicated to “furthering global democracy” owns stakes in the manufacturer of Louis Vuitton’s iconic Birkin bag, a cigarette manufacturer and a luxury Swiss watchmaker.

Like a tank on the battlefield, “ESG itself is a moving target, constantly shifting in the light of changing societal attitudes, technology and the scientific understanding of risk,” the Index Industry Association

As corporate America scrambles to quantify its efforts to do good and index providers churn out ever more benchmarks, it’s raising two elephant-in-the-room questions: What exactly are the social and financial merits of the scores, whose purpose is to catalog the financial risks a company faces over its environmental, social and governance practices? And are retail and institutional investors growing skeptical of the entire premise?

“Ask each of your 25 neighbors to define what good means, and you’ll get 25 different measures,” said Aswath Damodaran, a professor of corporate finance and valuation at the Stern School of Business at New York University. Which means, as Bentley Kaplan, an ESG researcher at index provider MSCI,

Enter what we might call “green blurring.” If greenwashing, a concern of European regulators and the Securities and Exchange Commission, refers to funds that confuse or mislead investors by touting do-good credentials that aren’t clear or backed up by their holdings, green blurring can be defined as the collision of goals that make sense according to a benchmark but don’t vis-a-vis related values — or common sense. Green blurring allows a fund to include certain stocks that might help prop up a fund’s returns despite being unlikely to meet many investors’ idea of sustainability. It’s one way a cluster bomb maker in Bangalore can show up in an ESG fund devoted to carbon reduction and climate improvement.

“At one level, investing is more difficult” with ESG, said Rick Redding, the CEO of the Index Industry Association, a trade group and lobby in New York. “I’m not sure investors always understand exactly what they’re buying.”

Defining the problem

The murkiness starts with the sustainability moniker. While purists argue that ESG is not the same thing as impact investing, ethical investing, sustainable investing, green investing, mission-related investing or other like-minded niches, it’s all pretty much the same quiver of arrows in the minds of ordinary investors. Only which quiver? Which arrows?

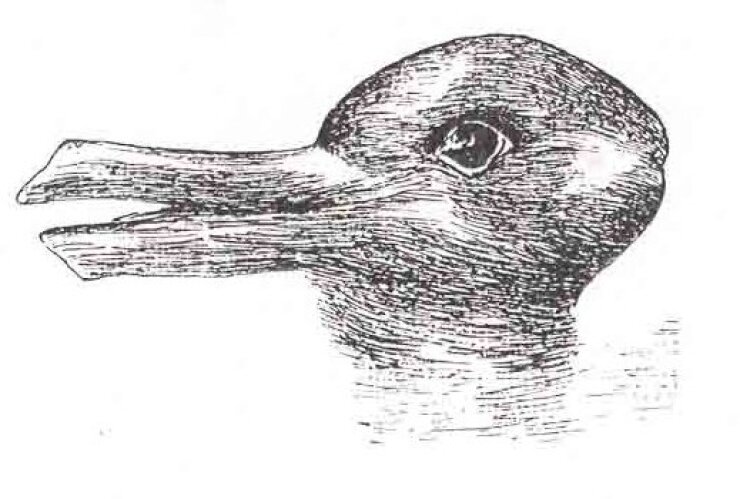

What we’ll call the ESG ecosystem, including sustainable and impact funds, is akin to philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous drawing (you see a duck, I see a rabbit), but multiplied across myriad dimensions.

“ESG means different things to different people,” said Hortense Bioy, the global director of sustainability research at ratings provider Morningstar. “I’m not sure we can come to an agreement about what is responsible investing, ESG investing, impact investing.”

As financial advisors increasingly field questions from clients over how to sync their values and beliefs with their retirement portfolios, philosophical puzzles are emerging. Good advisors routinely counsel clients to strip out their emotions — for example, not to panic sell when the market dips — yet the ESG premise is predicated upon feelings about issues (investors opposed to firearms won’t own funds with gun stocks, for example).

What’s more, feelings — expressed as attitudes, beliefs and perceptions about what’s important — vary across societies and cultures. They differ within industries and among demographics (pro-life individuals won’t invest in a company that supports abortion rights). And they’re constantly shifting, depending on what’s happening in the world.

This all means that companies that report efforts to reduce their carbon emissions — like the cluster-bomb maker — can have a notion of “sustainable” that’s very different when compared with funds that avoid defense companies.It’s how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is prompting some portfolio analysts and advisors to urge clients to reconsider defense stocks as a good for protecting sovereign states and international law. And it’s how, with the Supreme Court poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, companies like Amazon and Citigroup might find themselves excluded from certain governance indexes over their policies of reimbursing employees for out-of-state travel expenses for abortion.

The hype

Data, scores and metrics are supposed to be rock-solid quantitative measures that erase ambiguity. But the welter of benchmarks and profusion of issues they track only make things confusing.

“Most investors are not aware of 99% of the indexes out there,” said Redding. How many gauges are there? Redding said it was unknown but estimated tens of thousands. “Unlike the S&P 500 that people have coalesced around, with ESG, investors don’t agree on what all of the factors are,” he said.

Or understand the basic ESG premise.

“There can be a positive outcome,” said Michael Young, the manager of education programs at the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, a trade group and lobby. “But ESG is not trying to make the world a better place.”

Still, a March 2022

The guess might not be misplaced.

“I can take two stocks in a fund, rebrand as ESG and charge higher fees,” said Witold Henisz, a management professor at the Wharton School of Business and the founder of its ESG Analytics Lab.

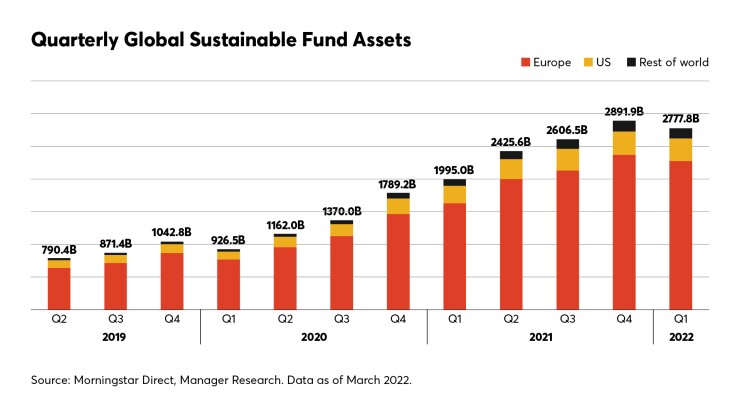

The inexorable rush by corporations, ratings agencies, benchmark providers, asset managers and funds to look at everything through an ESG lens accelerated at the start of 2021. Globally, funds claiming to focus on sustainability, impact, environmental, social and governance factors held nearly $2.8 trillion in assets as of March 2022, with 82% in Europe and 12% in the United States,

Last year, investors poured nearly $70 billion into U.S. sustainable funds, a 35% increase over 2020’s level, itself more than double the total for 2019 and nearly 10 times more than in 2018,

But in the first three months of 2022, investors put in less money for the fourth quarter in a row. Inflows dropped to $10.6 billion, less than half the record $22 billion in the year-ago period. Within the decline, investors are shifting less into equity ESG funds and more into sustainable bond funds, the rating firm said. Despite the turn, asset managers continue to launch new equity funds.

“The index providers and mutual fund and ETF marketplace are incentivized to create new indexes and products,” said Don Bennyhoff, the chief investment officer of Liberty Wealth Advisors. “It’s creating all these different choices that confuse investors and advisors.”

The recent slowdown in flows may expose fault lines in the ESG premise. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “has fundamentally changed the landscape” for stocks in European defense companies, a Feb. 28 report by J.P. Morgan said. “With regard to the sector’s ESG credentials, more investors may accept that ‘defence’ is needed to preserve peace and democracy, driving a re-rating” of defense industry stocks in ESG portfolios, lead analyst David Perry wrote.

The

“Index providers don’t just create indexes to have them — it’s driven by what investors want,” Redding said. It’s mainly institutional investors, such as large pension funds with sustainability mandates, and shareholder advocacy firms that are driving the trend — and filtering it down to ordinary investors.

Last year, an activist hedge fund backed by BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street won a battle to install three directors on the board of Exxon Mobil, with the aim of reducing the energy giant’s carbon footprint. On April 30, nearly half of independent shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway comprising just over one in four shareholders voted in favor of a greenhouse gas reduction

In the echo chamber of the ESG industrial complex, sustainable investing is starting to look like the vastly complex world of baseball analytics. Just as sabermetrics slices and dices tiny data points ad infinitum to evaluate a player’s performance — and has taken over the game — sustainability ratings scour anything and everything measurable in a company, then put the data through algorithms to come up with scores. The E in ESG is driven by hard data — it’s relatively easy to determine how many tons of carbon a manufacturer is spewing out. But the S and the G are much squishier. All that makes the ESG lens more like a jumbled pile of eyeglasses, each with a different prescription.

“The E, S and G make it seem like it’s a homogenous strategy,” Bennyhoff said. “But it’s not.”

In lock step with the corporate embrace of sustainability, the number of

But there’s no standard system of data or metrics for measuring a company’s performance on a given issue. A 2020

“Investors are unable to properly assess companies' performance on environmental, social and governance criteria and pinpoint material risks because of a lack of standardized data, a factor that may hinder the growth of ESG investing,” S&P Global

“This is a feature of ESG, not a bug,” NYU’s Damodaran said. “Is it possible to have standard metrics and data? Certainly not.”

Take the Democracy International Fund. Dedicated to “shifting capital flows toward democratic countries,” it uses a

“Some of our biggest fans are RIAs (registered independent advisors) who want to give their clients access to this space,” said Richard Rikoski, the chief economist at Democracy Investments. James Stoker, a director in the Austin, Texas, office of Graystone Consulting, a wealth management unit of Morgan Stanley, said that some energy companies that wouldn’t rank high on climate change score well on board diversity and hiring practices. “A lot of it’s gray: You just have to do best efforts around this stuff and ask, ‘what are we looking at?’”

Back to the Deutsche Bank fund that holds the tiny stake in Mindtree, which also makes software and is part of an $18 billion conglomerate with interests in engineering, construction, manufacturing, technology and financial services. The Solactive index it tracks initially excludes companies involved in controversial weapons, such as cluster munitions. But the fund’s 99-page

DWS Group, which is majority owned by Deutsche Bank, referred questions about its fund with the Mindtree stake to Solactive, the indexer. “Mindtree is included in this index as it is already a member of our ESG screened index series as it does not violate any of the exclusion criteria,” said Maria Seifert, a Solactive spokesperson. “This is already sufficient to be included in the index composition.”

On May 31, German authorities

Still, SIF’s Young said that with ESG, “there’s only more to come. Because there’s so much information out there that hasn’t been collected and shared.